When ‘My Truth’ Becomes Fake News: How ‘Daw’ Fuels Misinformation in the Philippines

Fake news thrives in noise — loud claims wrapped in vague words like "daw" or disguised as "my truth." In this blog, I reflect on the recent congressional hearing where vloggers apologized for spreading false information, the role of social media algorithms, and why accountability doesn't stop with content creators. Sometimes, an apology isn’t about regret — it’s about survival. And sometimes, the truth is quiet, steady, and easy to miss.

I was sitting on a worn-out bench at the tennis court, sipping a 3-in-1 Nescafé while waiting for my daughter to finish her training.

The court’s dull thuds from rackets hitting balls filled the air, while scattered conversations from other parents hummed in the background. It was the perfect moment to gather my thoughts — and this morning's blog couldn't have come at a better time.

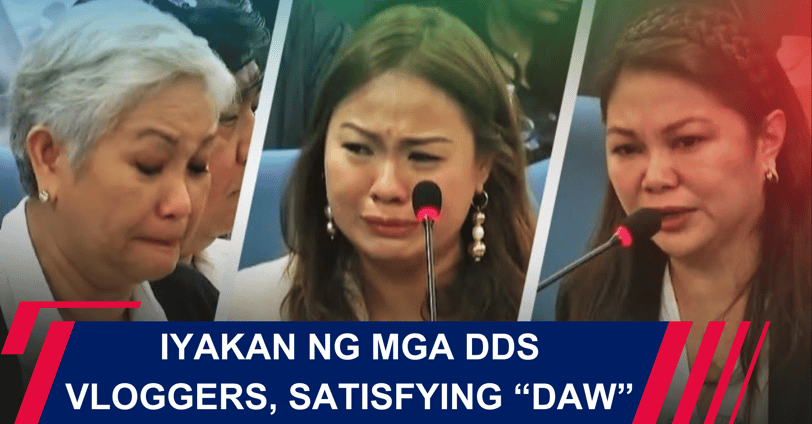

The recent House Tri-Committee hearing on fake news has been stuck in my head. Vloggers breaking down in tears, apologizing for false claims, and defending their posts as "my truth."

It reminded me of something I've often seen — not just online, but in casual conversations among friends and family.

“Sabi daw…”

“May nagsabi…”

“Allegedly…”

It’s that familiar dance where people avoid owning their words, clinging to vague qualifiers to escape accountability. These phrases turn gossip into something that feels like truth — and that’s where the danger lies.

As I sipped my coffee, I wondered: How often have we excused false claims by convincing ourselves it’s “just our truth” or “just something we heard”?

Maybe more often than we’d like to admit.

When 'My Truth' Becomes Fake News

MJ Quiambao Reyes sat before the House Tri-Committee, defending her claim that extrajudicial killings linked to Duterte's drug war were a “massive hoax.”

Her explanation?

"It’s my truth."

That phrase bothered me.

There’s a difference between standing by a personal opinion and presenting something as fact. Yet Reyes blurred that line, treating her belief like it carried the same weight as evidence.

I’ve seen this happen outside politics, too.

Maybe you’ve heard someone insist that a relative’s health scare was caused by a rumored vaccine side effect — even when doctors say otherwise. Or maybe a friend claimed a neighbor “definitely” cheated on their spouse because someone “heard it from a friend.”

It’s easy to fall into that trap. Sometimes, we’re so convinced by what we feel is true that we forget to ask if it actually is.

That's what made Reyes' defense unsettling.

When lawmakers pressed her for evidence, she had none. She admitted she couldn’t prove her post. Yet even as she apologized, there was hesitation — as if she wasn’t sorry for being wrong, but sorry she was called out for it.

That’s the tricky thing about justifying misinformation.

People cling to their version of the truth because letting go feels like losing an argument — or worse, admitting they misled others.

The Power of 'Daw' as a Shield

Krizette Chu knew her post was questionable.

She claimed there would be mass resignations in the police and military after Duterte’s arrest — a bold statement with no evidence to back it up.

When lawmakers asked her to explain, she didn’t deny it. Instead, she said she added the word "daw."

That one word was her defense.

It’s a familiar tactic. I’ve heard people do this countless times — casually sharing rumors, then shrugging off responsibility because they added "sabi daw."

But here’s the thing: adding "daw" doesn’t erase the damage.

People still believed Chu’s claim. Some may have shared it as fact, while others felt uneasy about the country’s stability because of it. Even with "daw" attached, the story had already left its mark.

That’s the danger of "daw."

For Filipinos, the word disappears as a story spreads.

“Mars, bakla daw si Mark, sabi ni Jennifer.”

At first, there’s hesitation — a hint that it’s just a rumor. But pass that story to a few more people, and "daw" quietly vanishes.

“Alam mo bang bakla si Mark?”

The same happens when the story starts as a question.

“Mars, bakla ba si Mike?”

Later, it becomes:

“Alam mo ba sabi sakin ni Jennifer, bakla si Mike.”

From interrogative to declarative. From rumor to fact real quick.

And before long, poor Mark is just another victim of a story that spiraled out of control — the truth lost somewhere along the way.

Chu’s defense may have sounded clever in the hearing, but it’s the same excuse I’ve heard at dining tables, tricycle terminals, and neighborhood stores.

It’s never harmless.

The Justification of Misinformation

Some content creators know exactly what they’re doing.

During the hearing, both Krizette Chu and MJ Quiambao Reyes defended their posts by claiming they were “raising awareness” or “sharing what people needed to know.”

It’s a clever excuse — one that makes misinformation sound noble.

I've seen this pattern before. Someone spreads a rumor, then masks it as concern.

“Alam mo, hindi ako sigurado pero... narinig ko lang... nag-aalala lang ako para sa kanila.”

It sounds harmless at first — even thoughtful. But more often than not, that “concern” is just a cover for spreading gossip.

Vloggers like Chu and Reyes played a similar game. Their posts weren’t framed as solid facts, yet they knew those posts would stir emotions and draw attention. Then, when questioned, they hid behind phrases like “I was just asking questions” or “I just wanted to raise awareness.”

But here’s the thing — planting doubt is just as damaging as spreading lies.

A neighbor whispering “Hindi naman ako sigurado, pero baka nga may babae si Mang Tonyo” doesn’t need proof. The damage is done. Even if the rumor started with hesitation, doubt lingers — and soon enough, that uncertainty turns into belief.

It’s the same online.

A vlogger doesn’t need to prove their claim when they can frame it as “just something people should think about.”

That’s how misinformation keeps finding a way to slip through — dressed up as concern, disguised as curiosity, yet just as destructive.

Echo Chambers and Social Media’s Role in Fake News

All three vloggers — Krizette Chu, MJ Quiambao Reyes, and Mark Lopez — admitted something troubling during the hearing.

Their posts weren’t based on verified facts. They relied on “what people were saying online.”

In other words, they trusted the noise inside their own echo chambers.

That’s the problem with social media — it’s designed to make us feel right. Algorithms feed users content that matches their beliefs, creating a space where ideas bounce back and forth, louder each time.

And the more you hear something, the more believable it sounds — even when it's wrong.

I’ve seen this happen firsthand on Threads.

Lately, I’ve noticed many fellow Kakampinks calling Threads our “new home,” convinced that the platform has become a safe space for like-minded people. At first, it felt true — my feed was flooded with posts from other Kakampinks, sharing thoughts, ideas, and messages of support.

I was happy to see it. It felt comforting — like we had carved out a space where our voices mattered.

But here’s the problem.

It’s not that Threads belongs to us — it’s that the algorithm is feeding us what it thinks we want.

Out of curiosity, I searched the hashtags used by the DDS. Turns out, they were saying the exact same thing — claiming Threads as their new platform because their feeds were just as packed with posts from their side.

Both groups felt like they had taken over, yet neither had seen what was happening on the other side.

That’s how social media tricks us. Algorithms create bubbles that make us feel like our ideas dominate the conversation — when in reality, we’re just seeing reflections of our own beliefs.

It’s comforting — but dangerously misleading.

This false sense of dominance fuels misinformation. When everyone around you is saying the same thing, there’s less reason to question it — and more reason to assume it’s true.

That’s why content creators like Chu, Reyes, and Lopez believed their own posts so strongly. They weren’t just spreading falsehoods — they were trapped in a system that kept feeding those falsehoods back to them.

Performative Apologies and Emotional Manipulation

“Sige po, mag-apologize po ako. Sige po, fake news po ako.”

Mark Lopez’s words may have sounded like an admission, but listen closely — it didn’t sound like regret.

There’s something about the way he said it that feels off.

"Sige po..." — a phrase Filipinos often use when they feel cornered. It’s the language of someone who’s tired of arguing, giving in just to get it over with.

"Mag-apologize po ako..." — polite, yet distant. It felt more like he was checking a box than genuinely taking responsibility.

And then, “Fake news po ako.”

The words felt like surrender — not accountability. Almost as if he was saying: “Fine, if you want me to say it, I’ll say it.”

That’s the tricky part about these congressional hearings.

Sometimes, apologizing isn’t really a choice.

In front of someone like Rep. Benny Abante — whose presence alone can be intimidating — refusing to apologize carries real risk. One wrong move, and you’re facing a contempt citation.

For someone like Lopez, a forced apology may have felt safer than pushing back.

It’s less about regret and more about survival.

It reminded me of how kids sometimes apologize when they know they’re about to get punished.

“Sorry na po...”

Not because they understand what they did wrong — but because they’re hoping to avoid what comes next.

You say sorry para hindi ka mapalo ng nanay mo.

(I wish this worked for my adoptive mother.)

That’s what Lopez’s words felt like.

His tears — and those of Krizette Chu and MJ Quiambao Reyes — may have been real. Maybe the pressure got to them.

But part of me wonders if they also knew something else — that sometimes, crying makes people stop asking hard questions.

Accountability Beyond Content Creators

The problem with fake news in the Philippines goes beyond individual vloggers.

For years, figures like Mocha Uson and Drew Olivar have played a significant role in shaping this disinformation landscape.

They didn’t just spread false claims — they worked to convince Filipinos that mainstream media couldn’t be trusted.

News outlets were labeled biased and corrupt, while Uson, Olivar, and their followers painted themselves as the only source of real information.

And for some, it worked.

People who once relied on traditional media began turning to these self-proclaimed truth-tellers — trusting their words more than journalists who spent years building credibility.

This distrust gave social media influencers an alarming kind of influence. Facts were easily dismissed if they came from mainstream outlets, while anything posted by these so-called “truth crusaders” was treated as gospel.

That’s why the House Tri-Committee didn’t just confront the vloggers — they also called out the platforms that allowed this mess to spread.

Facebook and TikTok were issued show cause orders for ignoring previous hearings, signaling that lawmakers are now shifting their attention to the enablers of disinformation.

And they should.

While content creators are responsible for what they post, social media platforms decide what gets amplified.

Algorithms reward engagement — not accuracy — so the most outrageous claims often rise to the top, drowning out reliable information.

The worst part? Platforms usually act after the damage is done.

By the time a false claim is flagged, it’s already been shared thousands of times. Correcting it becomes an uphill battle — like trying to clean up a mess long after it’s spilled.

We’ve seen this during elections and heated political moments. Outrageous stories spread like wildfire, yet platforms often wait too long to intervene.

This is why accountability can't stop with content creators. Social media giants — the ones designing these engagement-driven algorithms — have to take responsibility, too.

Because when influencers like Uson, Olivar, Chu, Reyes, and Lopez succeed in convincing people that only they hold the truth, social media feeds become battlegrounds where falsehoods thrive — and real information gets buried.

The Legal Consequences of Fake News

Spreading fake news isn’t just careless — it can get you into serious trouble.

In the Philippines, Republic Act 11469, also known as the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, makes it a criminal offense to create or spread false information during emergencies.

The law was introduced at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when panic-driven rumors flooded social media. Stories about military takeovers, fake lockdown schedules, and fabricated crisis reports spread faster than authorities could respond.

And it wasn’t harmless.

False claims caused panic buying, hoarding, and unnecessary fear. Some people skipped critical medical treatments because they believed social media posts that claimed hospitals were “unsafe.” Others rushed to ATMs after hearing fake reports that banks were about to shut down.

That’s the danger of fake news — even a single post can trigger real-world chaos.

The law makes it clear: disinformation isn’t just unethical — it’s punishable.

But holding people accountable isn’t always simple.

The challenge lies in proving intent.

Vloggers like Krizette Chu, MJ Quiambao Reyes, and Mark Lopez knew this. They used qualifiers like "daw", claimed they were “just sharing what they heard,” or insisted they were “just asking questions.”

And that’s where it gets tricky.

These defenses — vague enough to avoid direct blame — make it difficult to prove that someone intended to mislead others. But that doesn’t mean they’re innocent.

Whether the intent was deliberate or careless, the damage is the same.

False claims — especially in moments of crisis — fuel confusion, endanger lives, and undermine trust.

Fake news isn’t just reckless noise online. It’s a risk that can follow you offline — to a courtroom, or worse, to someone who believed the lie and acted on it.

Final Sip of Thought

My cup of 3-in-1 Nescafé had long gone cold.

The thuds of tennis balls hitting rackets felt distant now — my mind still stuck on everything I had written.

Fake news thrives because it’s loud. It taps into what people want to believe and drowns out the quieter voice of truth. That’s why it’s so effective — and so dangerous.

Vloggers like Krizette Chu, MJ Quiambao Reyes, and Mark Lopez played a part in spreading false claims. Influencers like Mocha Uson and Drew Olivar made things worse by convincing people that the media couldn’t be trusted — that they were the only ones with the real truth.

But accountability doesn’t end with them.

Social media platforms, with their engagement-hungry algorithms, are part of the problem. And so are we — the people who hit “share” without asking questions.

I’ve seen it happen too often — posts filled with "daw," vague claims, or sensational headlines spreading faster than facts can catch up.

The damage isn’t always obvious. Sometimes, it’s a neighbor quietly worrying about a false crisis. Other times, it’s a family torn apart by rumors that spiraled out of control.

That’s why we can’t just shrug it off as "Wala namang mawawala kung i-share ko."

There’s always something — or someone — at stake.

As I stared at my empty cup, I realized this — truth is rarely loud.

It doesn’t demand attention the way fake news does. But if you pause long enough, it’s always there — quiet, steady, and waiting to be heard.

Contact us

subscribe to morning coffee thoughts today!

© 2024. All rights reserved.