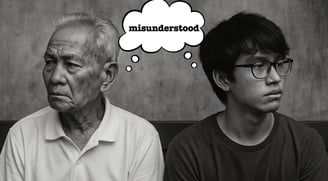

The "Weak Generation"? A Reflection on Filipino Youth, Strength, and Misunderstood Resilience

Are the younger generations really weaker — or are they simply surviving a world we never had to? In this personal reflection, I explore the roots of the “weak generation” label often thrown at Filipino youth. From parenting shifts and mental health stigma to economic pressure and evolving values, this blog challenges old assumptions and asks: what does strength look like today? Backed by research, real-life insight, and quiet honesty — this isn’t a takedown. It’s an invitation to ask better questions.

Yesterday, while waiting for my coffee, I overheard two older men talking.

It was one of those public conversations where people talk louder than necessary, half venting, half sermonizing. I wasn’t really listening—until one of them said, loud and clear:

"Bakit ang mga bata ngayon, mahihina?"

It’s not the first time I’ve heard that.

I’ve seen it online. Heard it from neighbors. Read versions of it cloaked in concern, frustration, or nostalgia.

But that moment stuck with me.

What does mahina really mean? Weak how? Compared to what? Or who?

So I made another cup of coffee when I got home and sat with the thought. Not to debate it. Just to understand it.

Because every time someone says “Mahina ang kabataan ngayon,”

I find myself asking the same thing—

Are they?

Or are we just using an old definition for a new kind of strength?

The Blame Keeps Getting Passed Down

We’ve seen it play out many times.

One generation survives something terrible. A war. A dictatorship. Widespread poverty.

They raise their children with the intention of giving them a better life. A softer one, maybe. More peaceful. More stable.

And when those children grow up and no longer look like the warriors they were, they’re called mahina.

It starts with the Silent Generation, those who lived through the Japanese occupation and post-war scarcity. They were told not to cry, not to complain, not to dream too much.

They learned to follow rules because questioning authority might get you killed.

They saw survival as the only goal.

Then came the Boomers, born during or just after all that wreckage. They grew up in a time of rebuilding — politically, emotionally, spiritually.

They didn’t have much, but they had structure. Discipline. Respect for hierarchy.

They raised their children to behave, to study hard, to obey.

Then those children — the Gen X kids — started asking questions.

Started staying out longer. Talking back. Thinking for themselves.

Suddenly, they weren’t strong. They were rebellious.

But what were they really rebelling against?

Maybe the silence. The emotional distance. The pressure to be composed but never heard.

Then came the Millennials, raised on hope and the promise of opportunity.

But they entered adulthood during financial collapse and political fatigue.

They were mocked for being idealistic, laughed at for being emotional.

Too expressive. Too dramatic. Too online.

Now, they’re raising Gen Z — a generation that doesn’t just speak up, they refuse to suffer in silence.

They’re honest when they’re tired. Loud when something feels wrong.

They challenge what we accepted.

And for that, they’re called weak.

But here’s the thing no one wants to admit:

We fought for them to have it easier.

And now we resent them for not being broken by the things we were forced to endure.

We call them mahina when they cry.

We call them mahina when they struggle.

We call them mahina when they ask for space, rest, help.

But here’s the irony:

The moment they answer back, they’re no longer weak. They’re disrespectful.

So which is it?

Do we want them to be silent, obedient, afraid — or do we want them to be strong?

Because it’s starting to feel like we don’t really want strength.

We just want them to suffer quietly.

And maybe the problem isn’t who they are.

Maybe it’s the world they’re growing up in — one we never had to survive ourselves.

Same Soil, Different Storms

Maybe the problem isn’t who they are.

Maybe it’s the world they’re trying to survive.

The older generation grew up with rationed rice, handwritten resumes, and discipline that came with belts. They survived blackouts, brownouts, and news censored by power.

They walked through literal storms.

So they think pain must look the same to count.

But today’s generation? They live in a different kind of storm.

The kind that doesn’t flood your house, but floods your head.

They wake up with five group chats demanding their time. They scroll past wars, tragedies, and suicide notes before breakfast. They apply for jobs online and get ghosted without even a rejection email.

Everything’s instant.

But nothing’s stable.

There’s a study from Ateneo that talks about this split — how Filipino generations are shaped either by politics or by technology. The older ones are called the political generation — molded by dictatorship, martial law, and social control. The younger ones belong to the technological generation — raised on real-time information, global conversations, and nonstop noise (Archium Ateneo Research).

What was once shouted in protest is now typed into a hashtag.

What was once endured in silence is now named, posted, and challenged.

It’s not about who’s stronger.

It’s about what they had to learn to survive.

Older generations were taught to keep it in.

Younger ones were taught to let it out before it eats you alive.

We say they’re soft.

But are we forgetting they grew up in a world that never shuts up?

There’s another layer to this — economics.

Some people love to say, “Nung panahon namin, isang trabaho lang, buhay na ang pamilya.”

That was true then.

It’s no longer true now.

These kids juggle freelance gigs, project-based contracts, short-term work — and still get told they’re lazy.

But what kind of future are we offering a generation who can’t even get regular employment?

And yet we shame them for not thriving in a system that doesn’t welcome them.

Someone on Reddit once said Gen Z isn’t even that good with computers anymore.

Not because they’re dumb — but because everything’s automated now.

They're used to things just working. They weren’t taught to open the hood and fix things. (Reddit Thread)

So yes, same soil.

But completely different storms.

And we keep forgetting that strength looks different depending on what kind of storm you're trying to survive.

Debunking the Myths About Gen Z Filipinos

Let’s talk about the labels we keep throwing around.

Because if you scroll through any comment section where Gen Z is mentioned, you’ll almost always find the same words.

Sensitive. Tamad. Reckless.

But when you look closer, you’ll see something else.

“They’re too sensitive.”

What they mean: “Hindi sila marunong magbiroan. Ang bilis mapikon.”

What’s actually happening: They’re setting boundaries.

They’re learning to say, “That’s not okay with me.”

According to a regional study on Gen Z across Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, younger people aren’t reacting out of offense — they’re expressing values. They want fairness, inclusion, and respect in their daily lives (WARC – Debunking Gen Z Myths).

They’re not trying to cancel everything.

They just don’t want to stay quiet about what hurts them.

And maybe that’s not fragility.

Maybe that’s self-respect.

“They’re tamad.”

The most tired criticism of all.

We say they don’t want to work. That they want instant success.

That they give up too easily.

But here’s what we don’t talk about:

They’re working. Sometimes multiple jobs.

Sometimes in roles with no benefits, no job security, and no future.

According to global and local data, many Gen Z Filipinos participate in freelance work, gig-based platforms, and digital entrepreneurship. It’s not that they’re lazy — they’re adapting to a work economy that no longer rewards loyalty the way it used to (LinkedIn – Alan Leach).

We say they’re not working hard enough.

But they’re wondering why they’re still poor, even when they are.

As one writer puts it, “Will you work hard for a very low wage, knowing that much of the profit will go to others, and at the end of the day, you're no less uncertain about tomorrow?” (The Myth of the Lazy Poor)

We gave them a world where hard work no longer guarantees stability.

Then we judged them for not pretending it still does.

“They’re fearless and reckless.”

Some say they jump from job to job.

That they post too much. Quit too fast. Speak up too soon.

But here’s what I’ve learned from reading what they say, and listening in when they talk to each other:

They’re not reckless. They’re trying to figure out where they feel safe.

In the same Southeast Asian study, one Gen Z participant said:

“We have our share of anxieties, which is why we constantly explore different experiences to find spaces where we feel safe and supported.”

(WARC – Debunking Gen Z Myths)

It’s not fearlessness.

It’s courage, in small daily acts.

To show up when your chest is tight.

To speak up when your hands are shaking.

To stay in the room when your mind is telling you to run.

They’re not fearless.

They’re just tired of pretending they’re not afraid.

What Filipino Psychologists Actually Say

It’s easy to talk about the youth when you’re not the one listening to them.

But psychologists do.

And when I read what they’ve observed, it didn’t sound anything like the usual complaints I see online.

It didn’t sound like mahina.

Studies show that many young Filipinos today value something called self-transcendence — concern for others, for the environment, for community.

In one study, 80% of Filipino youth actively try to reduce their negative impact on the world. That includes making eco-conscious choices, supporting social movements, and trying to live with intention and care (UMak Universitas, HRM Asia).

That’s not weakness.

That’s awareness.

That’s empathy in motion.

They’re also entrepreneurial.

Not in the old-school tindahan sa kanto way — though some still do that — but in building side hustles, freelancing, monetizing skills, and finding workarounds to a system that barely opens the door for them.

They’re practical.

They want purpose and income to exist in the same sentence.

And they’re not afraid to make their own path if the road ahead is blocked.

They’re emotionally aware, too.

We might joke about them being “too soft” or “too online” — but the truth is, they’re more willing to talk about what hurts them. What triggers them. What keeps them up at night.

That’s not fragility.

That’s honesty.

They’re not pretending to be okay when they’re not.

They’re not hiding their grief behind a strong face just to keep up appearances.

And that’s something older generations never really had the space to do.

But here’s the part I loved the most:

Filipino psychologists say lakas ng loob is still there.

So is diskarte sa buhay.

These aren’t lost traits — they’ve just changed forms.

Maybe we don’t see them hauling buckets of water or riding jeeps to job interviews in worn-out barongs.

But we see them pushing through burnout while still helping out at home.

We see them figuring out how to pay bills with three side gigs and a prayer.

We see them protecting their peace like it’s the only thing they can control.

(Filipino Youth Concerns Study, Sikodiwa Substack)

So no — they’re not mahina.

They’re just surviving a different world.

With different tools.

And maybe, different scars.

We soften the blow.

We protect.

We hold them before they fall too hard.

Especially Gen X and Millennial parents — many of whom grew up with absentee parenting, tough love, or emotional distance.

They wanted to do better.

They wanted to love louder.

But sometimes, love becomes a shield that blocks the small pains that teach bigger lessons.

On Reddit, one Gen X user asked: “Did we overcorrect?”

Did we try so hard to protect our kids from the trauma we experienced that we accidentally took away the grit that came with it? (Reddit Thread)

That question lingers.

Because you can’t develop emotional muscles if you’ve never had to carry anything heavy.

And now we look at Gen Z and ask: “Why are they so soft?”

Maybe because we never gave them space to fail without rescuing them.

Maybe because we taught them to avoid discomfort — but then scolded them for not being comfortable with pain.

It’s not just about parenting either.

It’s also how schools are structured. How policies avoid discomfort. How cancel culture cancels growth.

We’ve created a world where they can’t afford to make mistakes — and then wonder why they don’t feel strong.

But strength doesn’t come from never falling.

It comes from falling — and learning you’re still worth loving after.

And if we never gave them a safe place to land,

maybe that’s on us.

Mental Health Isn’t Weakness — It’s Honesty

Somewhere along the way, we were taught to keep quiet about what hurts.

That to cry was shameful.

That to name your sadness was to make it worse.

That to talk about pain was a sign you were already losing.

So most of us didn’t talk.

We worked through it. Prayed through it.

Or buried it somewhere deep enough to function.

But Gen Z is different.

They talk.

And for that, they’re seen as weak.

But here’s what the numbers show:

One study found that 17% of Filipino teens aged 13 to 17 had attempted suicide at least once in the past year.

Seventeen percent.

And that was in 2015.

It’s likely worse now.

Mental health professionals in the Philippines call it an epidemic (Inquirer Lifestyle).

They’re not exaggerating.

Another study shows that Gen Z Filipinos are dealing with climate anxiety on top of everything else — social pressure, family expectation, online comparison, and academic stress.

And all of it affects how they sleep, think, eat, live. (Nottingham Repository)

Still, in many Filipino homes, mental health is treated like a passing mood.

You’re not depressed. “Napapansin ka lang.”

You’re not anxious. “Kulang ka lang sa dasal.”

Or worse — “Ang arte mo.”

There’s a phrase we keep throwing at each other: “Kaya mo 'yan.”

And sometimes, yes — it helps.

But other times, it becomes a way of silencing real pain.

Not to uplift, but to dismiss. (Camella Melocoton)

So when Gen Z talks about their mental health, I don’t see weakness.

I see something a lot of us never had the courage to do —

to say out loud, “I’m not okay.”

To go to therapy.

To rest without guilt.

To name what they’re carrying.

That’s not a red flag.

That’s wisdom.

And if we can’t see that,

maybe it says more about us than it does about them.

Redefining Strength Across Generations

The more I think about it, the more I realize this isn’t about weakness at all.

It’s about the kind of strength we’re used to seeing — and the kind we don’t always recognize.

For Boomers, strength looked like obedience.

You followed the rules. You didn’t talk back. You worked hard, kept your head down, and earned your place through sacrifice.

We — Gen X — were raised to be independent.

We walked home alone. We cooked our own meals. We figured things out because no one was going to hand us the answers.

We became skeptical — of systems, of promises, of people in power.

We didn’t always talk about what hurt.

We just learned to survive it.

Millennials had to be flexible.

They came of age during recessions, layoffs, and instability. They learned how to start over, pivot, side-hustle, and smile through exhaustion.

They were told to chase their dreams, but also to pay the bills.

And now we have Gen Z,

growing up in a world where everything is visible, constant, and loud.

They learned to protect their energy. To rest. To ask for help. To say no.

They’re building strength through boundaries, not blind endurance.

So maybe it’s not that they’re weak.

Maybe it’s just that their version of strength doesn’t look like ours.

They don’t brag about powering through.

They talk about knowing when to stop.

They don’t pride themselves on staying silent.

They speak up — even when their voices shake.

And that takes strength too.

We’ve been taught that strength means carrying heavy things and never complaining.

But these kids?

They’re asking, “Why am I carrying this in the first place?”

They don’t want medals for suffering.

They want space to live.

To breathe.

To feel.

To try.

What if we’ve been using the wrong measuring stick all along?

And what if the courage to unlearn our idea of strength

is the strongest thing we can do now?

So Let’s Ask Better Questions

We keep asking, “Why are they weak?”

But maybe that was never the right question.

Because baked into that question is the assumption that something’s wrong.

That they’re broken.

That they failed to live up to a standard they didn’t create.

Maybe we’re asking it not out of concern, but out of disappointment —

disappointment that they don’t hurt the way we did,

that they refuse to suffer silently the way we had to.

But what if, instead, we asked:

What are they trying to survive that we never had to face?

What kind of world did we leave behind for them?

What do they know now that took us decades to understand?

Maybe they’re not weak.

Maybe they’re just done pretending they’re okay for people who never asked if they were.

We don’t have to agree with everything they say.

We don’t have to love every trend or understand every outburst.

But maybe we can stop treating their softness as a flaw

and start seeing it as a form of resistance —

a refusal to grow numb.

And when someone says again, “Mahihina ang mga bata ngayon…”

maybe all we need to do is pause,

sip our coffee,

and ask a better question.

Because if we’re not even willing to listen,

what kind of strength are we really modeling?

Contact us

subscribe to morning coffee thoughts today!

© 2024. All rights reserved.